Note: My review of Sophie Kemp’s Paradise Logic for Chicago Review of Books.

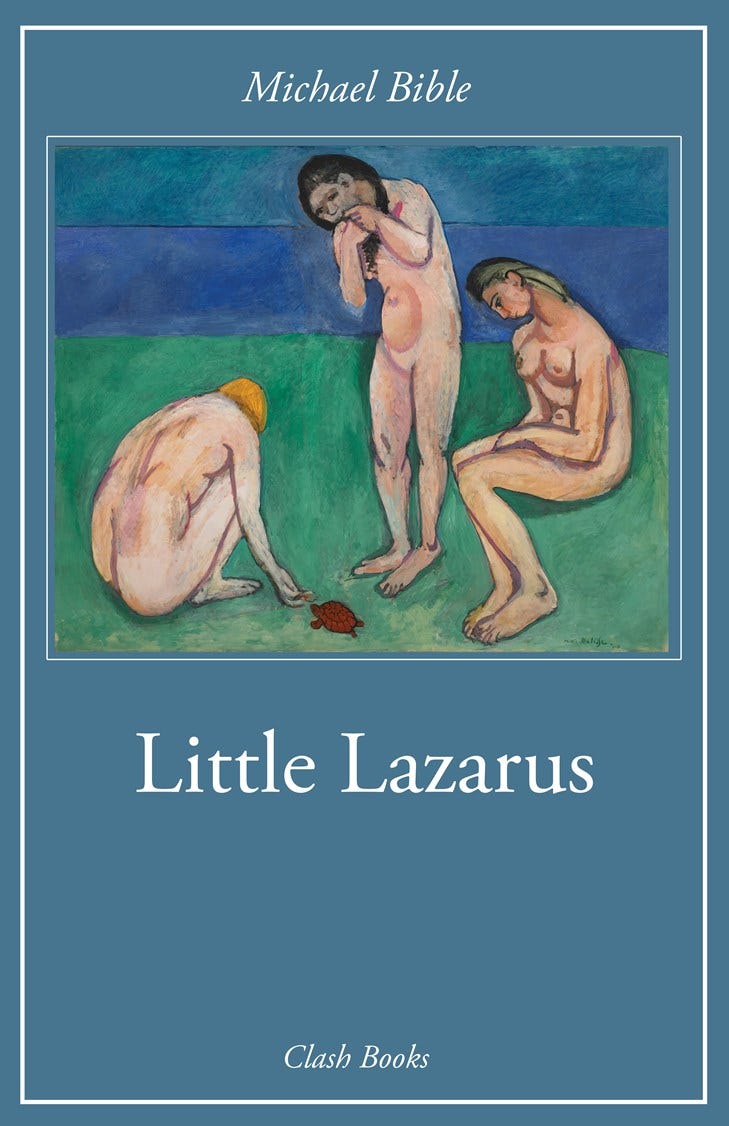

Little Lazarus. By Michael Bible. Troy, NY: CLASH Books, 2025. 154 pp. $16.95.

Tortoises are slow and quiet; this tale involving two tortoises has these two qualities, and together they give it an appealing dignity. The quiet is achieved by the plain style which has no grand cadences, but the slowness, more of a mystery, is something to do with plotting and the distance of the narration. An “overture” begins with the first flowering of the universe, and the end of the story is some hundreds of years after our time, so as a strict issue of years elapsed relative to page count, the novel moves extremely fast. Slowness has to do with the author’s patience. It’s a sad story he’s written which is to be suffered as much as savored, and in its not entirely linear ordering one can sense the care that went the stitching and patching, the selecting of the mostly sombre tones. The author is Michael Bible, who has published three previous novels with the independent press Melville House, and written journalism for VICE, The Guardian, etc. Little Lazarus is a curious novel in which slices of life make up a larger slice of Life.

Francois and Eleanor, teenagers in Harmony, North Carolina, might be in love. Eleanor’s sister Abby is definitely in love with Francois, and troubled Eleanor with her therapist Dr. Holland. They are drunk, driving her Jeep on a hill that has a dip over which a fast car can fly. Crossing the street is a traveler and small businessman nicknamed Seersucker, with his tortoise Lazarus, who has apparent clairvoyant powers if you pay a fee. These two are known in the town, so when Eleanor went to New York City and found a pet tortoise in the hallway of a restaurant, which she took with her, she named him Little Lazarus. She brought him back to Harmony, where he gave her and her family purpose, and where he will live long after her disappearance right before college. But for now, and in some sense for ever, she is in the red Jeep hurtling over the hill. She doesn’t want to go home (always a bad sign), and smitten Francois is at her command. This is how Bible has it: “Here is where past becomes future (. . .) It’s too late to stop now.” The story will be all about them, but also not, because the perspective is not strictly human. The two tortoises will be followed across time and space as they watch the follies and cruelties of their various owners, only ever nodding and blinking. They have human intelligence, it seems, but there is very little they can do to intervene.

The narration of Little Lazarus, whether by the omniscient storyteller of the overture or by Francois or Eleanor, is much like a film voiceover. Solemn, a little melancholic, able to take the occasional comic angle, but never telling jokes. If those two talk like they’re in the movies, it’s because they’ve seen a lot of them, and if one vaguely wishes for the singular phrase and gets instead the near platitude, Bible’s odd story does partly redeem everything it contains. The teenagers share a moment sitting on the hood of the Jeep in the morning sun after a party, and one feels one has been here before, but that may be the intention: “I joined her and we sat there in silence for what seemed like forever.” Bible is after the monumental feeling of such passages in adolescence, which would not be so monumental were they not partly formed from cliché. Once the story gets going in the “Lazarus” section, the narration often works at a pace approaching plot summary, accelerated to get characters from A to B, with only a few well chosen details: “That evening Lazarus was loaded into a large work truck and driven north through Manhattan. The wind shifted and Lazarus could smell garbage, weed smoke, and stale perfume.” It never feels fast. The more languorous scenes are those which Bible knows will be memorable by virtue of their odd settings and juxtapositions, like Lazarus’ and his handlers’ first look at his new home, a huge penthouse in Manhattan. But generally, the novel could use more narrative variety. As the tortoises crawl their separate ways through the story, it starts to turn into a gallery of American outcasts and anomalies, and this can feel repetitious. “Walt was from a small town in the Mississippi Delta. A lean, tall stoner in expensive sneakers.” Not long after this, we get: “Quiet was from Arizona. His real name was Quatrain but people called him Quiet.” You feel that the author has a whole shelf of notebooks filled with these creatures in capsule biographies, ready to be dropped into any of his stories. But then there is something potentially poignant in the way they introduce themselves quietly, say a few words, and shuffle off. In other words, there is a point behind things, which when you see the author’s designs near the end will make itself felt.

The tortoises have something to do with the Cosmic Turtle idea, which can be left to more ambitious readers. As for the novel’s sound and sensibility, there are echoes of an American classic as in so many of Bible’s contemporaries: Hemingway, whose style has been sold as the way things really were or some kind of distillation, but is really the song of disappointment in this life. Hemingway is as manipulative as any writer, as the reader can learn in sober thought after the tears have dried up. If anyone has learned this manipulation from him it has been less conscious an education than the training in his sentences. Hemingway got his sentence style from the King James Bible, and Michael Bible, when the action starts, gets it from him, however indirectly. Ernest begat so many sons, and they their own, that you end up with these odd coincidences. Here is Eleanor in trouble: “He grabbed my hair and I hit him but he pulled harder and I hit him again in the face and he let go.” If Bible were quite as relentless and determined as Papa he would have changed that “but” into another “and”. He, Eleanor continues: “I ran outside and I kept running. It was freezing but I was running so fast that I wasn’t even cold.” Ran, running, running. Bible is using Hemingway’s mode to get through his story, but by contrast with the original we can see how much feeling there is in a “but” or an “even”. In these inflections Little Lazarus has its precious, fluttering life. Bible as Eleanor is on his way somewhere Hemingway would never go on paper, a lovesome sentiment with an archaic “for” he would never write: “I will be afraid no longer, for you will be there with me.” This is a cosmic communication, but also an old-fashioned, hopeful one, more earnest than Ernest. You can sense Bible restraining his instinct for humor and oddity throughout the novel, just enough to let this line read the right way. He has been well-disciplined, then. All his own manipulations depend on it.