Creation Lake. By Rachel Kushner. New York: Scribner, 2024. 416 pp. $29.99.

(Note: My review of Gillian Linden’s Negative Space for 3:AM Magazine can be read here.)

“Writing this book was like a drug high”, Rachel Kushner told the Guardian. This may explain why it’s not very good. Its faults are recklessness, a refusal to be coherent, and an excess of enthused ideas, some of them rather heady. Creation Lake is Kushner’s fourth novel, following Telex from Cuba (American expats during the revolution), The Flamethrowers (a Nevadan artist in the 70s gone to New York, then Rome), and The Mars Room (a woman from San Francisco starting a life sentence in 2003). One can see a kind of progress continued here, as the setting is now 2013, the summer of Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky”. Our narrator is a thirty-four-year-old American lady spy, formerly of the FBI, before that doing a PhD in rhetoric at Berkeley, before that God knows, who is now working for unnamed private interests, and goes by the name Sadie Smith. She’s in France, infiltrating a radical, possibly violent environmentalist group named Le Moulin which is based in the Guyenne in the southwest. Having seduced and secured an engagement to rich young filmmaker Lucien Dubois, she is staying close to the commune at his family home, using him to get to the leader, Pascal Balmy, and into their operations. The Moulinards are a bit dumb and of doubtful conviction, but they’re in contact with a clever former associate of Guy Debord, a veteran of ‘68 named Bruno Lacombe, who advocates a withdrawal from the modern world and insists on the nobility of the Neanderthals. He is apparently living in a cave on his property, but he gets out regularly to send his emails to the young revolutionaries. Sadie, hacked in to access them, may be the only one who reads them carefully, or with any appreciation.

The spy plot is lax rather than suspenseful, a pretext for everything else as much as a dedicated story. There aren’t many long scenes to settle into, because Kushner has a lot of Lacombe’s theories to get through, and Sadie has her episodes of personal history, as well as some snide comments to give on her travel observations. The sections within the six long chapters are short, turning quickly, and sometimes by free association, from Sadie’s intel, to her activities at Le Moulin, to Bruno’s emails, to her recent past, and so on. The novel is a dish with many ingredients that seem fresh enough, some of them exotic, which while they don’t clash, don’t really work together all that well. Here is a moment where Lacombe’s talk of prehistory may be influencing Sadie, where the novel finds an echo, if not a harmony. In Paris, Sadie is going for the “cold bump”, a way to meet Lucien as if accidentally. She has posed herself at a bar next to him while he plays pinball, and while he’s probably hoping she’s impressed by his game, she’s seeing something else: “it seemed to me that this posture, of man and machine, recalled some ancient form: a man behind the box that he steers—a plow perhaps, or a cart.” Elsewhere, when Kushner needs to connect Sadie’s idea about everyone’s essential self, their “salt” as she calls it, to Bruno’s notions about reentering the cave to find out who you really are, she apparently has no option but to have Sadie say it straight out: “Bruno did not call this essence that was deep inside of people the salt, but it was what he meant. He was talking about the salt.” (This seam should probably be on the inside.) Sadie, with a spy’s cynicism, gives out lots of these stabbing, staccato lines, which are meant to get right through all the delusions and appearances.

Those who enjoy weary observational comedy at dinner will find a lot to like in Creation Lake. “Clean diesel, clean coal. Add the word “clean” and boom—it’s clean.” More sophisticated yet, well-traveled Sadie explains that Italians take too much pride in their pastas, which are all the same, and that their wines all taste the same too. Oh, and cinephiles? They’re just “accountants” who don’t get that “the essential spark elevating [sic] a movie to art never derives from the low domain of ‘expertise.’” Her catching up texts with Vito, boyfriend to Lucien’s film collaborator Serge, are occasionally quite funny, as the two riff on each other’s loose words. Alone with Sadie, though, some readers might feel discouraged by the monologue that dips from jaded down to morose. For the first third of Creation Lake, there is another kind of language, one that Sadie, a disillusioned dropout from academia, has not quite shed, and it seems ingenuous by comparison with the deadpan mode. This is perhaps Sadie’s but one suspects also Kushner’s careful passage into the Lacombe material, the paraphrasing of his emails using terms like “complicate”, “unpack”, “a category, a trauma, a foreclosed victory”, and her commentaries, where she’s on about “bearing witness” and “push[ing] back against assumptions”. Once Sadie, or indeed Kushner, has facility with Bruno’s caveman concepts, this precious, cautious patter is finished, and she is never again so vulnerable. But the change does not seem to be by the design of the author.

It may be that Kushner is not all that bothered about language. Her strengths are more intellectual than literary: it’s the assemblage of history and politics in her novels, of ideas and experience, that impress, more than sheer talent. In a quick read of Creation Lake, which is meant to be read quickly (written as it is in what the publisher calls “short, vaulting sections”) you might feel the appropriate tremor calling you to the caves, where Bruno, reversing Plato, wants us watching the play of light on the walls. But another look here and there suggests that the disconcerted feeling was something else, that in fact you couldn’t quite trust this spelunking partner. The harness feels a little off, and you wonder about those knots. . . Whether owing to the natural high of writing, or just haste, or both, shoddiness was allowed to pass. Here is Sadie’s tricky seduction of Lucien: “‘What,’ he said, smiling, detecting a spark in my eye, which he read as a spark of my happiness, my interest in him, presuming my emotions in this moment, us staring at each other, mirrored his own emotions at this moment.” And her odd, stilted description of communal lunches at Le Moulin, “meals whose offerings hovered in the genre of the enchilada despite this being France”, rather undoes itself with that word “genre”. Worse, actually a little dispiriting, is Sadie’s allusion to her probable undergraduate reading. The first morning at the Dubois home, she sees the sunrise, and so sees it succeeded by the day: “For all its fame, rosy-finger dawn leaves no prints” [emphasis mine]. Didn’t Sadie, in the intervening years at Berkeley studying rhetoric, cover personification?

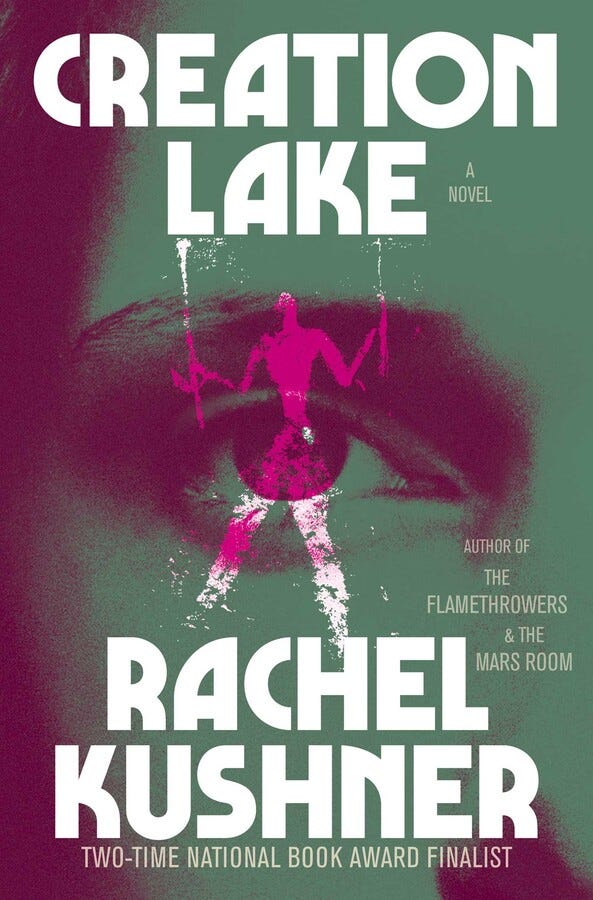

Sadie might have some buried grief, we learn, and maybe this is why she’s so often sipping at beer and white wine between her bitter aperçus. She is not meant by Kushner to be any more endearing than readers will find her. But, conflicted and possibly deluded as she may be, she is surely supposed to be a little more charming, and a little more interesting, as reported in an insinuating tone. When she’s done with her mission, she is to break away and leave without getting sentimental, but something ought to have fascinated her for the narration to be necessary, something, anything, of momentary and local brilliance, rather than Bruno’s global, epochal theories. That at least would have been some distraction from the dubious, dashed off prose. Kushner strains to find such a ravishing vision, as she had done more successfully in The Flamethrowers, using other characters’ anecdotes, things her narrator has not seen. Critics in their good will have squinted to find the good ones in Creation Lake, and have reported back in hushed excitement about the horror story from Bruno’s youth involving the Nazi occupation, which stakes a lot of itself on this penny dreadful line, given its own paragraph: “He had caught a dead man’s lice”. Whether impressed and disturbed, or suspicious of the way Kushner has gone macabre to signal depth and seriousness, one is left scratching one’s head. The novel is a little baffling, and to baffle is to deceive, as the French at least should know. One only need add that its cover is very good, and that it is now to be seen on the long list for the Booker Prize.