Pas de Trois

Roberto Bolaño's The Skating Rink

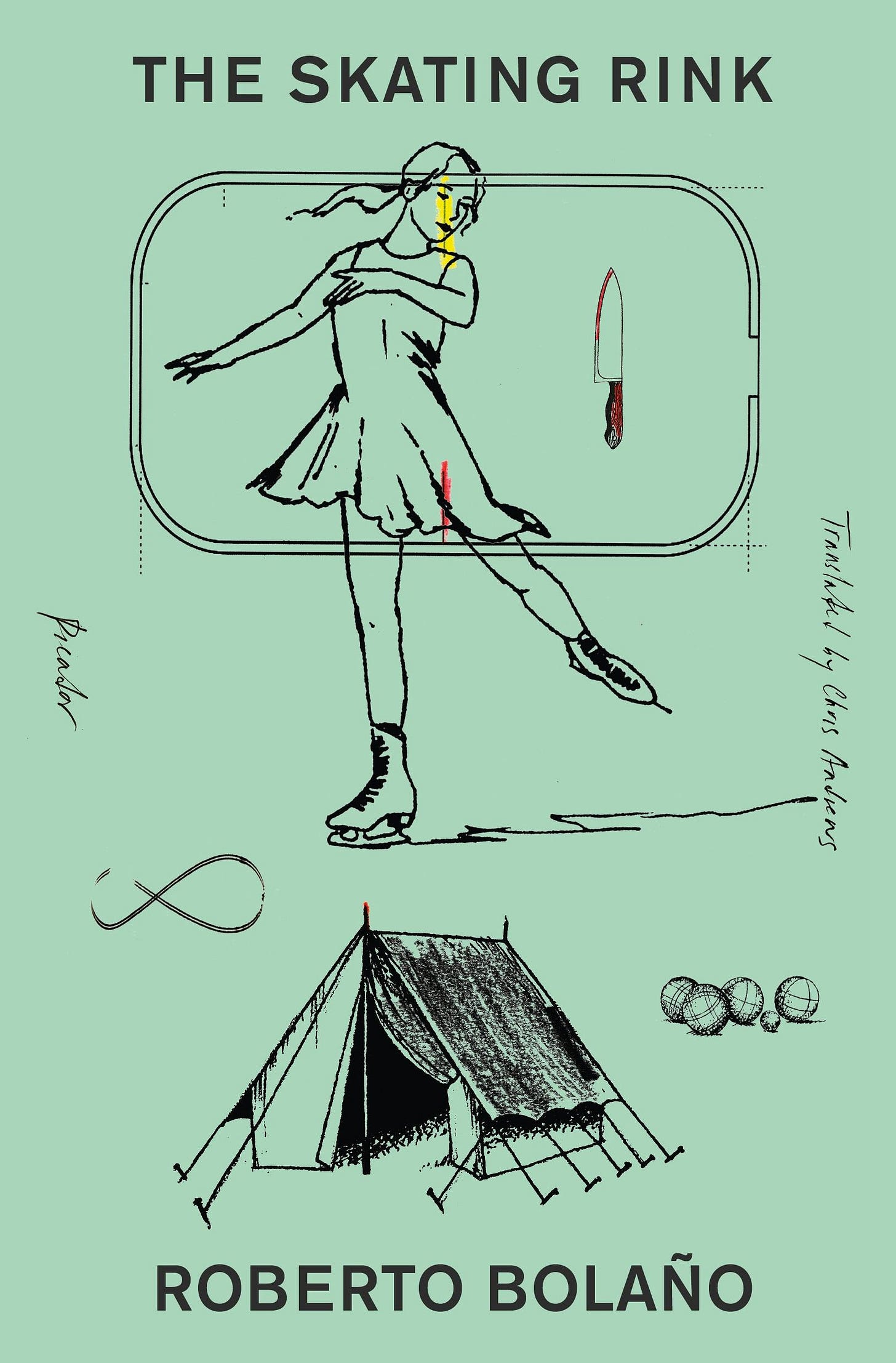

The Skating Rink. By Roberto Bolaño. Translated by Chris Andrews. New York: Picador, 2025. 192 pp. $17.

The reputation of the Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño, who died in 2003 at the age of fifty, rests mainly on The Savage Detectives and the posthumously published 2666. The Skating Rink, a much shorter work first published in 1993, was translated into English by Chris Andrews in 2009 for New Directions, and now reappears in the same translation from Picador. The tale, a murder on the Costa Brava in a town called Z, is spun as a waltz, with three tellers who are each given sections from one to seven pages long in rotation. Remo Morán, once a poet, runs a campground called Stella Maris, and some other tourist businesses. He has an ex-wife and a son, and he gets involved with a beautiful figure skater named Nuria Martín. Gaspar Heredia, whom Morán met in Mexico City, works at the campground as a night watchman, and becomes fascinated by a half feral woman named Caridad, who is often seen wielding a knife. Enric Rosquelles is a Catalonian who manages the Social Services Department for the socialist mayor, Pilar. He is so smitten by Nuria that after she is cut from the Olympic team, he builds her a skating rink in an abandoned mansion outside the town, the Palacio Benvingut, where he trains her for her return.

Readers of Martin Amis’ The Zone of Interest may be reminded of that novel by this one, and wonder if he read The Skating Rink on his way to figuring out his triple first persons narrative. The indignant, perhaps impotent Rosquelles shares with Paul Doll, Amis’ concentration camp commandant, a role of frustration, responsibility to a regime without firm belief, and romantic humiliation by another of the narrators, and all within what turns into a murder plot. Rosquelles’ voice is distinct where Heredia’s and Morán’s are similar in their weariness and ennui: he is supercilious, defensive, and finally comic. His grand efforts at winning over Nuria are farcical, and then, with time, uncomfortably believable, and the larger joke is his corruption of state funds, which he turns towards a very personal project, a covert pleasure dome which has been jealously inspired by Nuria’s enthusiasm for a Brook Shields movie, The Blue Lagoon. To Morán is given the occasional poetic vision, oddities like a sky turned pink, “the pink of an enlightened butcher”, or the days before the discovery of the body, which he calls “freshly painted inside and out”, and to Heredia is given the entrancing passage in which Caridad is followed by foot to the Palacio, and to the pristine, echoing ice rink at its center. The scene is a ceremonious unveiling, music followed down the halls, through interior courtyards and impossible circular rooms, through a sudden freezing draft and into the sight of the lone girl skating. Bolaño’s inclination, let alone ability, to record this strange, sinister beauty in an otherwise salubrious fictional world is a curiosity.

Chris Andrews evidently did a bang-up job transferring the highly varied tones from Spanish to English, in which latter language The Skating Rink comes out relaxed and flexible, with colloquial touches that never disturb. In the longish, sinuous sentences, with their gentle corrections and adjustments, the work takes its breath, and has an apparent ease, whatever it’s narrating: “When I think of those afternoons now, it makes me laugh, but I wasn’t laughing at the time, and even now, there’s often something strained about my laughter.” Such questions as why Morán’s laughter is strained are not to be answered, nor are they asked with much urgency, as the import is in the larger something that has caught up him and the other two men. There is an uneasy sense with each narrator that he is mostly missing the point, witnessing but not getting the purposes that the author has designed for him. Bolaño undermines his narrators, not just by using them to catch each other’s delusions and vanities, but with their own words. Each section uses its opening several words, a clause or two, as a section heading under the narrator’s name, and the repetitions of these openings puts them under scrutiny, plain and unassuming as they may be. The sections are never quite finished, as they always end in an ellipsis, which one expects to find annoyingly portentous after a while, but is actually rather effective . . . This gentlest of the terminal punctuation marks has a lulling effect, even after a scene of ugliness or jarring absurdity such as one finds in this novel. If one expects a comprehensive moral view of the crime from the triple perspective, one is to be disappointed. Instead there are oddly detailed accounts of how the campground is run, how Rosquelles got his job, or how Nuria stays fit for skating. Once more information comes out, the novel’s mundane particulars are shown to be irrelevant, as if these are the wrong narrators, or the wrong story. Bolaño unsettles, not with shocks or special effects, but languorously, carefully, with a patience in his formal scheme that seems not just novelistic, but also musical.