Curious Incidents

Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes: A Thrilling Casebook of Villainous Crimes

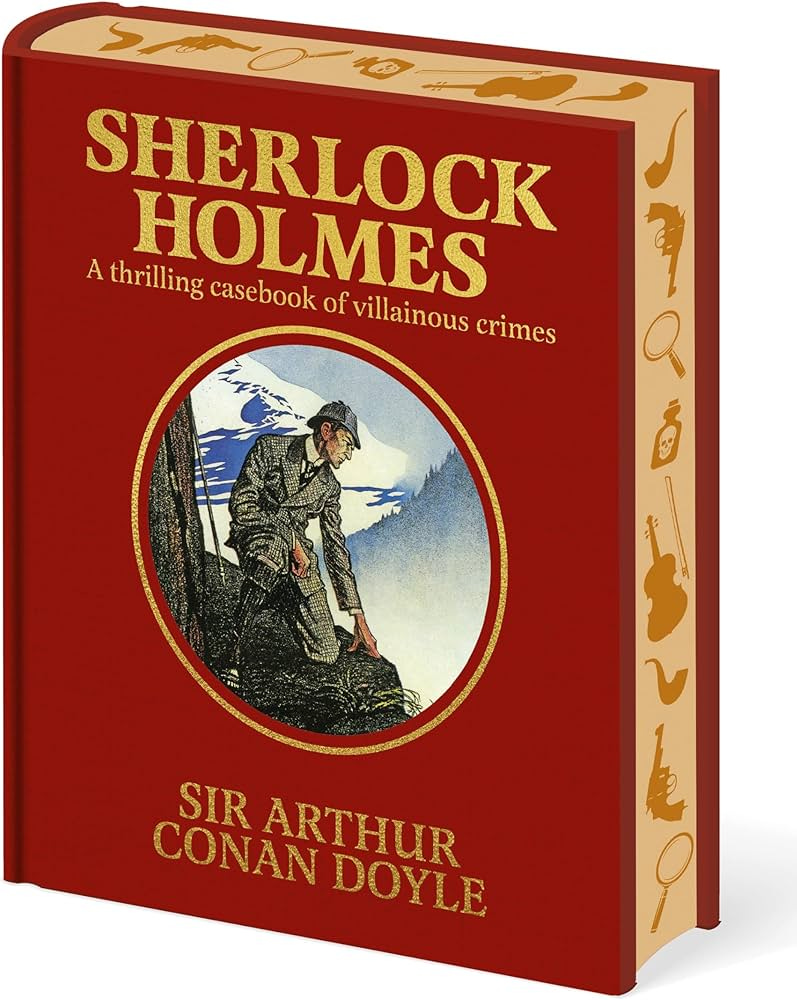

Sherlock Holmes: A Thrilling Casebook of Villainous Crimes. By Arthur Conan Doyle. London: Sirius Publishing, 2025. 304 pp. $24.99.

This anthology comprises the novel The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902) along with seven of the short stories from the early years, 1891-1893, all of which were originally published in The Strand Magazine, and it includes the original illustrations by Sidney Paget. There are many Sherlock Holmes editions, most more handsomely done; this one has the advantage of counterposing rather than segregating the longer and shorter works, which will tend to make one wish for the sake of the whole corpus that a couple batches of stories could be traded for more novels.

Doyle famously seemed to have killed Holmes in 1893, throwing him and Professor James Moriarty, grappled together, off a precipice and into the Reichenbach Falls. This allowed him to dedicate several years to his historical fiction, including the well thought of Micah Clarke, set during the Monmouth Rebellion. But in 1901 a friend told him about a Dartmoor legend involving a giant hound, they discussed it and its potential (deeply enough that Holmes would pay and acknowledge him for his contribution), and he adapted it for his and a returning Holmes’ purposes. For returning readers, the hound of hell might be less frightening this time, but the sounds and images of the Devonshire moors can thrill again, and in the senses current and archaic. The culprit seems pretty shifty from his introduction, and is named well before the end, so the whodunnit becomes a howdunnit, the question remaining whether there is something supernatural afoot.

In a piece for Lapham’s Quarterly, Michael Dirda notes that the Holmes novels can be “structurally awkward”, with their historical flashbacks, and finds the several chapters of The Hound of the Baskervilles during which Holmes is apparently absent “a little like Hamlet without the prince.” But Holmes was always theatrical, and his reappearance within the story, if not surprising, is triumphant for both author and character. Watson, meanwhile, has a chance to show his sensitivity to the “grim charm” of the craggy, menacing surroundings, and his ability to be severe as an interrogator of witnesses. The story, as ever, is in significant part about their odd friendship. Watson the writer confides himself “piqued by his indifference to my admiration and to the attempts which I had made to give publicity to his methods”, but as the ad hoc detective he is much pleased by the praise of his sleuthing and his reports sent back to London. Just before Holmes reveals himself, there is this passage which in the light of the whole story is either oddly conflating Holmes with the killer, or giving an accidental, absurd hint: “Always there was this feeling of an unseen force, a fine net drawn round us with infinite skill and delicacy, holding us so lightly that it was only at some supreme moment that one realized that one was indeed entangled in its meshes.”

The Hound of the Baskervilles obviously takes place before Holmes’ apparent death, and sometime after Watson starts publishing his accounts of their adventures. It is presumably placed first here because the stories include “The Adventure of the Final Problem” in which Holmes and Moriarty fall. The others are “The Red-Headed League”, “The Five Orange Pips”, “The Adventure of the Speckled Band”, “The Adventure of Silver Blaze”, “The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual”, and “The Adventure of the Reigate Squire”, and all can be found collected as part of either The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes or The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. These stories, cleverly plotted, built of Watson’s unimpeachable, disciplined prose, can bear a second reading. Hints and Holmesian phrases (“a three pipe problem”; an awful lot of “my dear sir” and “my dear fellow”) have a familiar ring, and the memory brings back partial solutions, but there are flourishes one enjoys as if for the first time, particular as the stories end, such as the news from a distant coast in the final paragraph of “The Five Orange Pips”, not just a shipwreck, but the “shattered sternpost of a boat . . . seen swinging in the trough of a wave, with the letters “L. S.” carved upon it”. This reader found only one logical quibble among these stories, regarding the abrupt termination of the patsy’s employment in “The Red-Headed League”, which surely raised suspicions unnecessarily, but he may have missed something there, and it should probably just be accepted that all these crooks, until we meet Moriarty, are cunning but not entirely thorough. Doyle does not have the time in a short story to create atmosphere as he does so well in The Hound of the Baskervilles, so one finds these minor mysteries a little brusque, satisfying to a rational appetite but not much more. They are dominated by Holmes’ patient talking through of his deductions. One wonders what could have come of “The Musgrave Ritual”, had it been taken further, seeing as the subterranean story within the story involving secret Cavalier artifacts is the kind of thing Doyle had treated in longer works. The legacy of the crown, discovered and re-hidden, could have served a function like that of the legend that threatens to recur in The Hound of the Baskervilles.

In “The Adventure of the Final Problem”, a “paler and thinner” Holmes calls on Watson and tells him all about the so far unknown, un-hinted at Professor Moriarty, giving this final story in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes a fuller and for Holmes more personal background than we have known in previous stories. We have that nearly mystical sense of secret designs which Doyle will get at again in the “unseen force” behind the scenes in The Hound of the Baskervilles, and with figure similar to the “fine net”, tactile but transparent. Here it is pictured by Holmes:

Again and again in cases of the most varying sorts—forgery cases, robberies, murders—I have felt the presence of this force, and I have deduced its action in many of those undiscovered crimes in which I have not been personally consulted. For years I have endeavoured to break through the veil which shrouded it, and at last the time came when I seized my thread and followed it, until it led me, after a thousand cunning windings, to ex-Professor Moriarty of mathematical celebrity.

Then we look at Paget’s illustration of the nemesis, stooped, dour, more a schoolmaster than even a professor—and isn’t the “Binomial Theorem”, on which the professor wrote his famous treatise, secondary school, not university level? But we have it on Holmes’ authority that this man is his equal. Watson catches a couple glimpses of Moriarty, but all knowledge of him comes through Holmes, in his precise description, and dialogue that he recreates and which we read in nested quotation marks. Like Holmes, Moriarty elegantly variates, and shows his hostility with haughtiness: “‘You crossed my path on the 4th of January,’ said he. ‘On the 23rd you incommoded me; by the middle of February I was seriously inconvenienced by you; at the end of March I was absolutely hampered in my plans . . .’” The story is a small masterpiece, in which Doyle’s hero is proven vivid enough to bring life to another, a shadow self, maybe, but more real than the lesser villains. A tall, thin man in black with rounded shoulders, clean shaven, balding, with sunken eyes, whose intelligence does not raise him above pettiness, just as Holmes’ does not raise him above showing off.

“The Adventure of the Final Problem” retroactively places Moriarty somewhere behind some of the criminal incidents that have interested Holmes. It apparently kills Holmes, births and kills Moriarty, and makes Holmes a sentimental figure, “the foremost champion of the law of their generation”, a superlative which strains and misrepresents his motivations, making Watson look a little silly. It is no longer than the usual stories but it has more latitude, which the other six here have conspicuously lacked. This was a fine ending, but it is a very lucky thing that Doyle could be persuaded to bring Holmes back from the turbid waters for The Hound of the Baskervilles, a longer Holmes work than he had yet written. The absence may have made the chronicler appreciate his subject more fondly, as it does for Watson within the novel. There Holmes reappears as an anonymous villain stalking Watson across the moors: he has been given a new dimension by the introduction of Moriarty eight years before, an idea of what he might have become if not a detective, so that when he approaches the hiding, misapprehending Watson, he is different kind of presence before the inevitable reunion:

Then once more the footsteps approached and a shadow fell across the opening of the hut.

“It is a lovely evening, my dear Watson,” said a well-known voice.